Yesterday I finally visited Death: a self portrait at Wellcome Collection. Jim, my friend Alex and I checked out Brains: the mind as matter last year and I remember leaving a bit underwhelmed, the actual exhibition not quite living up to its sexy marketing. It did what it said on the box; there were samples of brains in slices, mapped out in vessels and neurons with some blackened tumours thrown in for good measure. I suppose I wanted some more stylised or functional representations of what the brain could do as opposed to what it looked like. Perhaps the wet labs at Uni desensitised me to squidgy, floating samples in jars and curly slices of grey matter. Due to their fantastic advertising, Wellcome Collection gets crammed and for such a busy exhibition my companions and I felt that it was overly text-based rather than adequately visual, visceral or aural.

Despite that experience, I was super excited to see Death and I decided to go by myself. I am not one for exchanging ‘bants’ whilst viewing works of art, and I thought the subject matter called for a certain degree of introspection and contemplation. I mostly ended up contemplating whether or not I could surreptitiously cripple the people sheparding me along the line of closely displayed works with tiny, wordy descriptions. Every time I became involved in some degree of reflection someone would shove their pointy finger in front of my face and loudly declare their opinion. Oh my God! For the first time in my life, I wished there were some sort of audio guide so I could stand back without lining up and jostling my way to a corner to read a tiny plaque. Perhaps there was an audio guide and I just missed it? Wellcome, stop being so damned attractive!

Anyway, Death: a self portrait is a selection of works from the private collection of Richard Harris – a former antique print dealer who has spent the past 40 years building his own epic Memento Mori (a latin phrase, which translated warns ‘Remember you will die’). It is interesting to discover that Harris’ love affair with death stems from a keen interest in anatomy; if I had one critique of the exhibition it would be that it was primarily concerned with an anatomical depiction of mortality in the form of skulls and bones. Obviously this is a universal representation of death, but again I thought there might be more scope for exploration of that final moment that awaits us all, particularly in the more contemporary works. Is a photograph from an unknown source showing a Physician posing with an educational skeleton really a snapshot of a man considering his own mortality? I couldn’t help but feel that a more selective approach would have been more effective. To me an entire, tightly packed wall of sketches results in each sketch losing its impact. Strangely, when the exhibition ‘thinned out’ a bit towards the back of the gallery (and therefore could be viewed comfortably), the descriptions didn’t really do justice to the role those contemporary pieces play in our rituals concerning Death.

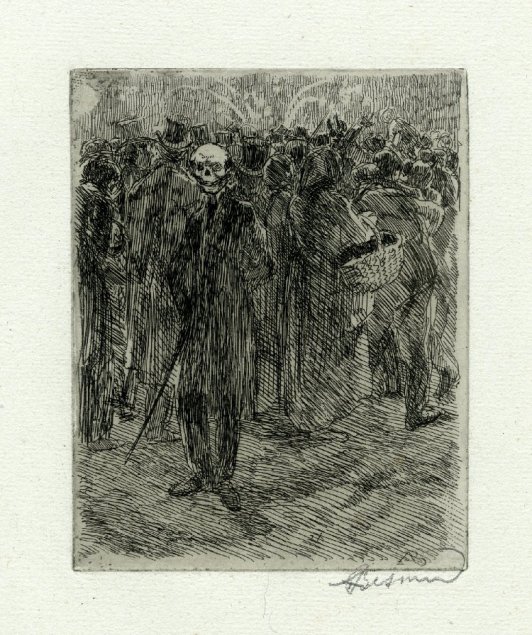

I don’t mean to sound like a Debbie Downer, and perhaps the perpetual crowd control issues unfairly influenced my experience. There were beautiful sketches and prints by some amazing artists, and clearly the back story accompanying each piece was part of what attracted Harris to them in the first place. The infamous contemporary work Are you still mad at me? by John Isaacs (1968) was satisfactorily visceral and shocking, in contrast to the refined and petite Japanese okimono carvings. My favourite was a tiny sketch produced in 1900 by an artist named Albert Besnard. It is called Dans la foule (In the crowd) and shows Death turning away from a throng of people enjoying a firework display… facing the viewer square-on with a lurid smile. Not only is it powerful and captivating, the written description finally gave me the words to describe why fireworks make me feel so lonely and sad. They are a symbol of transience – of fleeting beauty that blossoms for a moment then fades into nothing. Everyone is alone when they watch, no matter how big or enthusiastic the crowd. You can’t help but take stock and think ‘Where am I in my life, what the hell am I doing? Do I like it… does it matter?’ And always, Death is patiently and cheerfully biding his time, right behind you.

If you’re in London it is definitely worth a look, but I would really try to go during a weekday. Oh and a surreptitious crippling is probably going too far…a subtle elbow should suffice.